There’s a specific satisfaction in experiencing Sonya Sombreuil because she goes deep on everything. Not fake deep, like she’s trying, but deep deep. Thoughtfulness and intentionality stream into everything she makes, everything she does and says. Zoe Latta, one half of fashion brand Eckhaus Latta and one of Sombreuil’s oldest friends, describes Sombreuil as a conduit for something spiritual that even she, after decades of knowing her, is still mystified by. “I don’t mean that in a religious sense,” says Latta. “But her paintings, everything feels like it’s imbued with messages. The medium and the method might change but she’s always got something.” Sombreuil would never describe herself this way. She shuns anything self-congratulatory. But she does seem to be channeling something from somewhere. Come Tees, the brand she founded in 2010, is just one medium through which she interacts with, and challenges, the world.

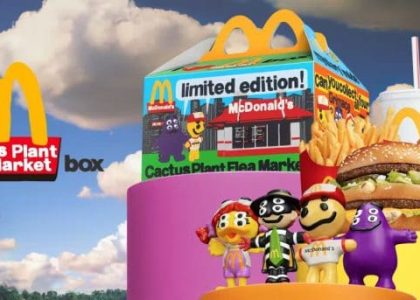

Come Tees pieces are works of art that you can put on your body: screen-printed T-shirts, hoodies, bottoms stamped with paintings, drawings, imagery, words, lyrics or references sacred enough to Sombreuil for her to put on a garment. Take one of her latest collections — tees that reference vintage rave fliers through poetic, nonsensical larks on heavyweight cotton. One of the pieces reads: “WHO AM I / THE SEER, THE SEEN, THE UNSEEN / HOUR OF THE STAR / 777 / PASSWORDS.” Her recent collaboration with Converse — which features Sombreuil’s take on the Chuck 70s, among other pieces — mimics collage with hand-drawn, heavy brushstroke visuals and a hanging tag, which is a photographic re-creation of a pin her dad gave her when she was a child. It says, plainly, “I’m an artist. Your rules don’t apply.”

Clothing is a form that Sombreuil, also a painter, finds appealing for sheer visibility’s sake — it opens up the possibility for an image that’s close to her heart to travel far around the world, like a mobile canvas. “I love the idea of being able to disseminate your work that way,” Sombreuil says. “Having people [experience it] who are maybe more like a peer, rather than a collector, rather than someone from the top tier of society.”

Her work, no matter the medium, carries that sensibility, from the childhood photorealist pig and chicken paintings in art class to the zines she made as a teen to Come Tees to the show she created for the Hammer’s “Made in L.A.” to the more abstract, colorful paintings she’s making today. Sombreuil thinks a lot about what it means to be an artist and what it should be.

“There’s identity, which is cool — I actually am down with the politics of it,” Sombreuil says. “And then there’s divinity. This is the first time I’m saying this out loud. But to actually be an artist, you have to be connected to spirit in that way, which exists totally differently for every being. I don’t mean to fire shots, but you know there’s so much s— out there that just is not on that level. It’s involved in a level of aesthetics or identification. And that’s a valid conversation, I don’t actually discredit that. It’s just on a different frequency.”

Sonya Sombreuil grew up in Santa Cruz, a daughter of two alternative-medicine doctors. Her dad and older brothers were into music — the former is a music and culture obsessive; he’s been described as the “most into-music person” people know who doesn’t play music professionally. Sombreuil’s mom, not unlike her, is the kind of person who goes through intense phases: The name Sombreuil is a kind of rose in French — her mom was really into roses around the time she was born.

Specialized interests always captivated Sombreuil: She was into what she calls a “profound form” of natural horsemanship; comics; books; ‘77 punk; ‘60s rock; the list goes on. “I had a pretty developed sense of what I was interested in,” Sombreuil says. “It’s sort of unflappable.” This sense of self was developed without the internet — Sombreuil, who is 36, came of age before that, really — and didn’t have an idea then that these highly specific genres or artists or movements she was drawn to often had entire cultures surrounding them outside of her small town. She sees the irony now: that someone who has always been searching for a sense of belonging was actually a part of something bigger all along. But back then, it made her attachment to the things she loved that much more intense. “Things felt very, very sacred to me,” she says. “I had a sense of almost proprietary, ‘I’m the only one I know that’s into this.’”

Sombreuil likes to joke that the first subculture she was a part of was just an after-school painting class. “It was a really rarefied, total kind of little subculture led by this woman, Celeste Baross,” she says. Sombreuil started in the class when she was 4 and went until she was 18. “That was my original identity. I was the artist within my family. I was the artist on the schoolyard, kids would line up for me to draw stuff for them. And that’s always been how I see myself. The way that people identify themselves has really changed. And that impulse of making things is the primary thing that I’ve been processing the world through the longest.”

That’s how Latta, who was in the painting class with Sombreuil as a teenager, remembers her then. “Sonya, for as long as I can remember, was the star,” says Latta, who as a teen made clothes with Sombreuil for fun and has collaborated with her on Come Tees projects. “It’s her perspective and otherworldly observance. There’s no status quo. There’s no normalcy. I do certain things, and I’m like, ‘Man, I’m really turning into this basic b—.’ Sonya has just defied all that. For always. Even if she smokes a cigarette or wears a Nike sports bra or something ‘basic,’ it’s still so alt and so considered and other. She’s not even trying.”

Sombreuil says she considers herself someone who exists outside of fashion. Making clothing just came from wanting to lace up herself, or her friends, or design merch for noise or punk bands she was into. It was also one of the only ways she could wrap her head around implementing her art in the world after she got out of college. Galleries seemed too obscure, too far away and out of touch with anything she was actually interested in. Come Tees was — and is — rooted in DIY process and ethics, though it’s grown too big for Sombreuil to do everything herself anymore with a 500-watt bulb on her four-color tabletop press. The work remains deeply rooted in personal references, and you get the sense that it is still very much for herself and her friends.

Everyone from Rihanna to Kanye to Lil Nas X has been spotted rocking her pieces. Collaborations with Levi’s, Ganni, No Sesso have inevitably expanded her audience. Sombreuil understands what participation in commercial entities means, she understands that it’s inevitable in a lot of ways working in this industry. But she continues to have faith in her work’s potential to uplift people and ideas that are rooted in radical politics or to be a contribution to a community she believes in.

One of Sombreuil’s most recognizable pieces is a shirt she made in 2020 to raise money for the Bernie Sanders campaign, which would become official merch for the camp (she had an in because her boyfriend worked for the campaign). The shirt features a young-ish photo of Sanders with the words “RAGE AGAINST THE MACHINE” around it like a frame. It got worldwide recognition, selling out again and again. But the shirt going mainstream made her a bit uneasy at first. “I’ve had a lot of reservations about using this space to talk about politics,” she wrote in 2020 on Instagram. “I’m aware the people I love see participation in electoral politics as a form of complicity. I’ve worried that it would counter my image as a supporter of radical politics and culture, and the deepness of those values. It took me a long time to understand and to engage with the Sanders campaign … On my own terms, I have researched and identified this movement for what it is: a people’s movement to dismantle corporate greed and its stronghold on society — primarily the justice system, healthcare and the environment.”

The Sanders shirt — and the dilemma it posed — is still something Sombreuil wonders about. She tells me she’s been interested in getting back to what she describes as image making. “I’ve been thinking about, sort of seriously, and sort of not, how much I love art that deals with anarchism,” she says, chuckling. Sombreuil still isn’t one for virtue signaling. But she has used Come Tees as a vehicle for mutual aid efforts for artists, organizations and movements since the beginning. The brand has raised funds for Watts Community Core via the artist Jan Gatewood and the South Central Local Chapter of the Los Angeles Tenants Union in collaboration with 8-Ball Community, among many other groups. “I was doing that when I had nothing,” she says. “I was sleeping on the floor of my studio and I was like, ‘I want to make something for this legal aid thing.’ I see myself as someone who is interested in all different cultures,” she says. “But they all sort of have to do with a kind of ethic around opposition.”

A Come Tees piece feels unlike other streetwear, which typically relies on graphics that Sombreuil describes as “little ideas that mutate really quickly.” Where internet culture is about people digesting and processing images at a certain clip, Sombreuil is interested in moving at a different speed: “my own.” “I only would go through that process for an idea or an image that I really cared about, which is sort of antithetical to streetwear culture,” she says. “A lot of it has to do with the constant iteration of ideas that are sometimes pretty banal — that’s something that I think is kind of cool about it,” Sombreuil says. “But for me, something has to be deeply important to my narrative for me to print it.”

And something about the specificity connects even harder. A Come Tees design is a peephole into Sombreuil’s mind. You can tell when she’s in a phase — obsessing over stars, flowers, cats or certain handmade figures — because whatever she’s into will show up in different iterations on the pieces. “Deep resonance is something that actually has a much broader appeal,” says Sombreuil. “It’s kind of a paradox, because in some ways, when you’re really specific, it can be niche. But on the other levels that you’re communicating on, it’s so broad.”

When we talked, Sombreuil was on multiple deadlines — finishing some paintings for a group show she’s going to be in with some of her studio mates and friends, the artists Mario Ayala, Devin Reynolds and Alfonso Gonzalez Jr., curated by Greg Ito in Hong Kong. Along with preparing for a show she’s going to be in with the artist Maia Ruth Lee at the end of the year. Not to mention, Sombreuil recently opened a small gallery, called Dream Child, in a Chinatown space she’s rented for nearly eight years. (The location has had many iterations under Sombreuil, including as a curated store called Classic Hits and as a studio space used by her friends, including the artist Clifford Prince King.)

So much of Sombreuil’s work is working with, and creating virtual or literal space for, the subcultures and small communities she’s always existed in. Being, as Latta described her, a conduit for her own message or that of others. She did this when she created her installation for “Made in L.A. 2020,” which showed in 2021. For the multi-part piece, she erected a physical venue in the Hammer, based on the artist-run spaces she came of age in. It included a gallery activation, featuring the work of artists Diana Yesenia Alvarado, Gatewood, Narumi Nekpenekpen and Yoma Ru; a storefront with limited-edition merch; a screening room featuring other artists; live performances and a fashion show by No Sesso as well. With Come Tees, she recently started a tape label called Lotus Tapes, which she says converges her “underground music superstars.” (Each cassette features an oil painting and patch by her.) She’s constantly exploring what this idea can look like, the most considerate way it can be done.

“When I moved to L.A., there was a big transition from waiting tables or bartending and making things for my own vanity or wanting to lace out my friends to when it was actually providing for me. But it was only on a sustenance level — I spent a long time living on the floor of my studio,” says Sombreuil. “In that time, I was really interested in people who lived a spiritual life that also involved radical politics. I don’t think that’s me. I don’t live outside of society in any way that those people did. But I ride for those people. And I wanted to be part of that. Come Tees has always been a little thing that satisfied me on a personal level. It’s like you’re transmitting your voice and certain other things are on that frequency.”

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.